A section of the looted Elgin Marbles

Ripping priceless marble figures from the pediments of Greece’s Parthenon cannot be classed as a safe, legal form of conservation, no matter how much money changed hands with the local corrupt authorities, an act never presumed to be honest. It was vandalism and theft. The marbles were not lying somewhere in England, but in Greece, where they were created. That it was carried out by a Scot, Lord Elgin, is shameful. It happened during England’s days of colonial empire, seen at the time as entirely entitled. The aristocracy are entitled to the best. We should stop calling them the Elgin Marbles, and allude to them for what they are, the Greek Marbles.

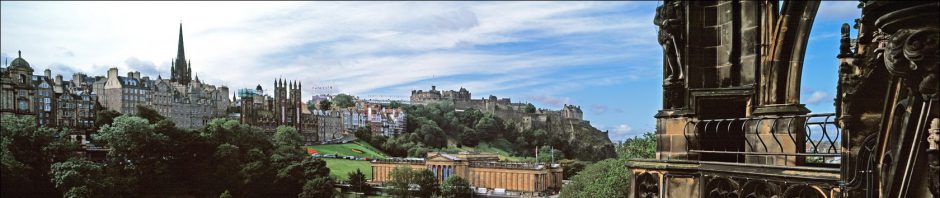

Statement of facts aside, the Marbles are set to return to Greece as the British Museum closes in on a landmark deal. It appears our own Scottish Museums hasted an end to the diplomatic banter by deleting a regulation that what is not Scots indigenous but taken from other lands can be returned. The log-jam was dislodged. The solution was always there for the taking, but the classic English attitude of superiority held it back – make high-grade copies for England’s British Museum, return the originals to Greece. (I have a perfect copy of one horse’s head in my garden, the one below. It weighs a ton, as does the original)

The marbles were taken from Greece to Malta, then a British protectorate, where they remained for a number of years until they were transported to Britain. The excavation and removal was completed in 1812 at a personal cost to Elgin of £74,240 (equivalent to £4,700,000 in UK pounds).

Times are a-changing, and it has grown harder and harder for the trust that ‘owns’ the sculptures to keep excusing the theft as ‘saving’ them as a ‘unique part of our common humanity’ – exactly the same limp reason given for Scotland to forego its civil and constitutional rights for a miserable regressive existence dominated by a false union with England – ‘we share a common humanity‘.

Built in the ancient era, the Parthenon on Athen’s Acropolis was extensively damaged by earthquakes. During the Sixth Ottoman–Venetian War (1684–1699) against the Ottoman Empire, the defending Turks fortified the Acropolis and used the Parthenon as a castle and gunpowder store. On 26 September 1687, a Venetian artillery round, fired from the Hill of Philopappus, ignited the gunpowder, and the resulting explosion blew up the Parthenon, and the building was partly destroyed.

The explosion blew out the building’s central portion and caused the cella’s walls to crumble into rubble. Three of the four walls collapsed, or nearly so, and about three-fifths of the sculptures from the frieze fell. About three hundred people were killed in the explosion, which showered marble fragments over a significant area. For the next century and a half, portions of the remaining structure were scavenged for building material and looted of any remaining objects of value

“The Acropolis was at that time an Ottoman military fort, so Elgin required special permission to enter the site, the Parthenon, and the surrounding buildings. He stated that he had obtained a firman from the Sultan which allowed his artists to access the site, but he was unable to produce the original documentation. However, Elgin presented a document claimed to be an English translation of an Italian copy made at the time. This document is now kept in the British Museum. Its authenticity has been questioned, as it lacked the formalities characterising edicts from the Sultan. Vassilis Demetriades, Professor of Turkish Studies at the University of Crete, has argued that “any expert in Ottoman diplomatic language can easily ascertain that the original of the document which has survived was not a firman”. The document was recorded in an appendix of an 1816 parliamentary committee report. ‘The committee permission’ had convened to examine a request by Elgin asking the British government to purchase the Marbles. The report said that the document in the appendix was an accurate translation, in English, of an Ottoman firman dated July 1801. In Elgin’s view it amounted to an Ottoman authorisation to remove the marbles. The committee was told that the original document was given to Ottoman officials in Athens in 1801. Researchers have so far failed to locate it despite the fact that firmans, being official decrees by the Sultan, were meticulously recorded as a matter of procedure, and that the Ottoman archives in Istanbul still hold a number of similar documents dating from the same period.” (Wikipedia)

Anti-Scot George Osborne, chairman of the British Museum and the former Tory chancellor who told Scotland it would not be allowed to use the pound sterling and then ran away, has drawn up a provisional agreement with Athens as part of a “cultural exchange”, a first step in repatriating the Marbles.

The move has come 200 years after the Earl of Elgin “appropriated” the treasured artefacts from the Parthenon in Athens. It comes after the National Museums of Scotland (NMS) reversed a policy that allows the repatriation of items from its 12-million strong collection – leading to hopes the British Museum would follow suit. Since 1866 the institution, based in Edinburgh, had stuck to a presumption against returning objects held in its collection. It is now adopting a procedure for considering “requests for the permanent transfer of collection objects to non-UK claimants”.

Now it has emeged that the British Museum and the Acropolis Museum in Athens are closing in on an agreement that would see the 2,500-year-old artefacts looted during the imperial era. returned over time to Greece as part of a cultural exchange, ending a feud over the historical artifacts that dates back to the 1800s. An agreement would see a proportion of the marbles sent to Athens on rotation over several years. In exchange, other objects would effectively be loaned to the museum in London, and Britain could also get plaster copies of the Parthenon sculptures.

A British Museum spokesman said: “We’ve said publicly we’re actively seeking a new Parthenon partnership with our friends in Greece and, as we enter a new year, constructive discussions are ongoing.” The Greek government has frequently demanded the return of the marbles, but the British Museum has previously claimed among other reasons that it has saved the marbles from certain damage and deterioration and has not acceded. The New Acropolis Museum in Athens, which is adjacent to the ancient site and completed in 2008 devotes a large space to the Parthenon, and the pieces removed by Elgin are represented by veiled plaster casts.

The development comes after the government rejected Tory peer Lord Vaizey of Didcot’s call for a law change to make it easier for UK museums to deal with restitution requests. While Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s colonial office has ruled out changing a law that prohibits museums from removing items they hold, a loan or rotation arrangement based on a cultural exchange may provide a way through that legal hurdle. But the reality is, they belong back in Greece. Full Stop. Imagine looting a pharoh’s tomb and calling it conservation of items that would have degraded over time. Mr Vaizey, chair of the Parthenon Project, which is working with the British and Acropolis Museums to find a solution, said an outcome is “finally within reach. “We have argued for a deal that is beneficial to both Greece and Britain, centred on a cultural partnership between the two countries,” a spokesperson for the project said. “This would see the British Museum continue in its role as a ‘museum of the world’ displaying magnificent Greek artifacts as part of rotating exhibits, with the Parthenon Sculptures reunited in their rightful home in Athens.”

The amended NMS policy states: “NMS’s collections reflect its diverse history and multidisciplinary nature, spanning the arts, humanities, natural and social sciences. Each of the five collections departments contains some objects that originate from outside of the United Kingdom. In exceptional circumstances, NMS will consider a request made by claimants located outside the UK to transfer a specific object or group of objects where the request meets certain criteria.”

An agreement would resolve a dispute that’s plagued Anglo-Greek relations since the foundation of modern Greece in 1832, and which even threatened at one point to add another layer to the UK’s already-complicated Brexit negotiations with the European Union. The objects including sculptured marble, including columns, pediments and 17 figures were removed from the Parthenon at Athens and from other ancient buildings and shipped to England by arrangement of Scots nobleman Thomas Bruce, 7th Lord Elgin, who was British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. By 1803 all of these were boxed awaiting shipment bound for Broomhall House, the family seat of the Earls of Elgin, three miles south-west of Dunfermline. Most of the marbles got back to Britain safely courtesy of the Royal Navy. Lord Elgin was less fortunate as he was captured by the French and held prisoner until 1806, fateful justice.

With much of the project financed by his wealthy Scottish heiress wife, Mary Nisbet, the final shipment of the Elgin Marbles reached London in 1812, and in 1816 the entire collection was acquired from Elgin by the crown for the sum of £35,000, about half of Elgin’s costs. Again, the thief lost out on the deal. The removal created a storm of controversy that exemplified questions about the ownership of cultural artifacts and the return of antiquities to their places of origin.

In 2004, Andrew Douglas Alexander Thomas Bruce, the 11th Earl of Elgin and Chief of the Clan Bruce, when asked to comment on the belief that the treasures are stolen property, replied, “Totally unfair and completely untrue,” before proceeding to explain that everyone in Britain “should be proud of what was done,” by his ancestor. The Earl added that in his opinion the 7th Earl had the express consent of the Ottoman Empire to remove the marbles. “It was an act of conservation, without parallel at the time.” How Elgin got consent could make the entire plot of a filmed drama.

It is a contradiction to argue, as successive earls of Elgin have and the British Museum too, that the Marbles were saved from potentional destruction, for if that is the reason there is no excuse to keep them in Britain now that Greece can look after them and in a specially designed museum.

A Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) spokesman said: “The Parthenon Sculptures in the British Museum are legally owned by the Trustees of the British Museum, which is operationally independent of government. Decisions relating to the care and management of its collections are a matter for the trustees.” (Legally is a gross overstatement.) Last month, the museum said in a statement it had “publicly called for a new Parthenon Partnership with Greece” and would “talk to anyone, including the Greek government about how to take that forward. We operate within the law (a way of saying they made up the law and will respect it) and we’re not going to dismantle our great collection as it tells a unique story of our common humanity.” But we are seeking new positive, long term partnerships with countries and communities around the world, and that of course includes Greece.”

And while on the subject of the misappropriated Marbles, let’s see the British Museum return artworks looted from Scotland including the Lewis Chessmen.

*****************************************************

Reblogged this on Ramblings of a now 60+ Female.

The British did the same sort of things in Australia 200 years ago. In one instance they killed a “rebellious” Aborigine who had been picking off their soldiers. He was a Freedom Fighter fighting against colonialists who invaded his land which had been his for 60,000 years.They then cut off his head and sent it back to a museum in England. It has finally been carried back to Australia by his descendants.

I certainly agree about the Lewis Chessmen, particularly as only a few are on display in London while the rest lie in the vaults. They may be made available for study but it is a long way for Scots to have to go to London to study artefacts which were found in our own country.

The Greeks were wronged twice over the marbles as it was the imperial power of Turkey which agreed to let the representative of another imperial power of the time, Britain, take away priceless examples of Greek culture and craftsmanship. Turkey had no right to give that permission and Lord Elgin had no right to accept it.

Just how ‘Scottish’ was Elgin? Though he bore the ancient name of Bruce, he was a member of the British establishment, as his behaviour demonstrates.

Looking back at your essay, Gareth, I am left wondering if anyone in the British /English government exhibits any examples of ‘common humanity’

I only found out last week, that the Bruces who took the Elgin Marbles and sacked the Summer City in China during the second Opium war were descendants of Robert the Bruce, and I felt disappointed that Scotsmen could do these things for theBritish empire

It was Thomas Bruces son who wrecked the Summer Palace in the 1860s if I remember correctly

In the 1930’s the sculptor Jacob Epstien was appalled to see, on a visit to the B.M. the marble figures being subjected to a good rubbing down with wire brushes and solvents to remove the ancient paint. So much for protecting the frieze from deterioration. He wrote to The Times on the subject and earned the emnity of the British establishment for his pains. The looting of the frieze was also the desecration of a war memorial. The Panathenaic Procession represents the Athenian dead from the battle of Marathon, each figure representing one of the fallen. Epstien throughout the inter war years was denegrated and insulted by the establishment. The attacks were to a large extent motivated by racism. The ultimate insult was the destruction of the sculptors major work, The Strand Statues. I hope that soon the Benin Brones will also be going home.