An occasional series on eminent Scots under-valued by the general public or forgotten.

Frederic Lindsay (1933 – 2013)

An independent novelist

There is any number of Scottish-born authors of detective fiction, a few full-time and very successful, but the best of them all is no longer with us, Frederic Lindsay. Not all his novels are detective thrillers but all represent literature of the highest quality rather than the best of pulp fiction. Lindsay was both highly respected by colleagues and publishers and partly ignored by the popular press.

Much of his prose leans to the poetic. There is an ebb and flow to descriptive passages that is immensely pleasing. The words he has his characters speak, whether protagonists or minor walk-on roles, is always spot-on accurate. No speeches between characters is interchangeable. He had a superb ear for dialogue.

He writes about hard working people living on the edge and fat, over-indulgent businessmen who rule the lives of those working people.

One quality had him stand out. All his adult life Lindsay was a fervent supporter of Scotland’s independence. He did his research and came to the only conclusion one can, the Union is an economic and political disaster for Scotland, makes a mockery of the democratic process, and licences the UK Treasury to keep Scotland’s wealth.

He was clever enough to shun shallow celebrity, to eschew the role of ubiquitous instant opinionist, the pawn of media agendas. Instead, he weaved his commitment to real democracy into his work. But he was quick to write a sharp letter to a newspaper editor correcting the lies of its columnists.

Rebuffing newspaper propaganda was a problem when the person writing it happened to be a fellow author, in particular one who praised Lindsay’s books. “I hate doing this and alienating a friendly reviewer!”

This happened in the case of Allan Massie, no lover of freedom for Scotland. In an acerbic riposte Lindsay demolished Massie’s uninformed dislike of SNP policies espoused in a Scotsman article. Massie never retaliated, but to be fair he continued to praise Lindsay’s novels. “Lindsay’s detective novels are unusual in that they gain in depth and credibility as the series progresses.”

I have a true story the measure of the man. When Alex Douglas Home was due to give a talk on a better deal for Scotland after the Conservative party’s proposal for devolution and an assembly was laid aside the young Lindsay did an audacious thing. He decided to test Home’s commitment face-to-face. At the time the public generally believed Home’s concern was genuine for the poor economic return Scotland gets from handing its wealth into a UK pot, the wealth often squandered.

Being no card carrying member of the Tory party, Lindsay dressed up as one in tweed jacket, brogue shoes, a stout walking stick, (barber jacket and green wellies today!) plus the de rigueur blue tie, to gain access to the meeting at which Home was main speaker. During the question and answer session Lindsay got his moment. He asked Home how he intended to keep his promise to give Scotland more powers.

In an effort to deflect the question and save Home embarrassment, his election manager began to answer for him. Lindsay slapped him down demanding his “constituent MP answer”, adding he had travelled miles to hear him! Unsurprisingly, Home spluttered and waffled making obvious his promise was personal not Tory Party policy. Predictably, once elected the Tories quietly dropped any mention of autonomy for Scotland.

As a writer Lindsay was chased and published by the biggest and best publishers in the land, Andre Deutsch one of them, such was the standing he enjoyed among the choosiest of choosy eponymous publishers. At the time of his sudden death, aged 79, Lindsay’s novels had just been introduced to an American audience. Fate takes no prisoners.

I met Eric, as family and friends called him, when he was a lecturer at Hamilton College of Education. I liked him immediately. He enjoyed a clever joke, but as a lecturer then myself I never considered that one day we’d work together on his first book as a filmed drama. At that time he’d written only poetry and some educational papers.

Brond, his first book, was published in 1983 by Edinburgh’s Loanhead publishers MacDonald, and was immediately hailed by critics as “a Glaswegian Day of the Jackal” and “like a political thriller written by Kafka”, a novel still high in the list of the ‘Best Scottish Novels Ever Published’.

It is a superb study of why power does not lie in Scotland, and how we are manipulated by our domineering neighbour. Outside R.L. Stephenson I had not encountered a Scottish writer who could write with a powerful political subtext and insight, and moreover, such authentic dialogue. Ever word, every nuance, you knew would have been spoken by the character he gave it to. There was metaphor and symbolism everywhere, his characters drenched in frailty and ambition. This was a writer who understood human psychology.

Lindsay was 46 years old when he wrote Brond. On hearing Hamilton College was about to close putting him out of work he realised that, “Unless I got down to writing something substantial, the assumption that I would one day write a novel could be curtailed by a bout of senility.”

He wrote three more novels, published between 1984 and 1992, each differed markedly in tone and subject matter. My favourite is A Charm against Drowning, the story of a disillusioned college lecturer agonised by a drug addicted daughter. For a dark tale it’s full of hope.

When he got the itch for another novel he was drawn to the true story of Detective Lieutenant John Trench of the Glasgow Police, who, in attempting to prove that there had been a miscarriage of justice in the Oscar Slater case, faced dismissal from the force and persecution by his ex-colleagues.

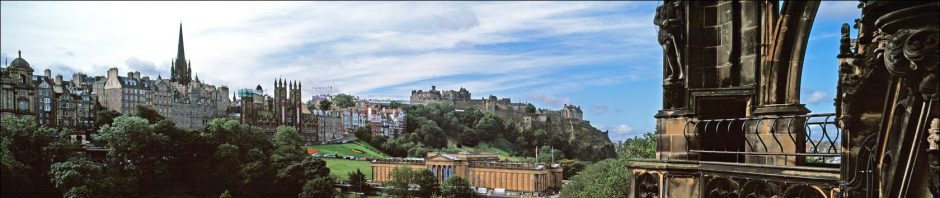

“Interested in the fate of the whistle-blower and the political background to the story, I moved the events to Edinburgh and to the present and turned it into the novel Kissing Judas. The central character was a police detective called Jim Meldrum only because that’s what the story required. As far as I was concerned it was a one-off book, a study in integrity and what it cost.

Then I had a call from my agent to say that Hodder & Stoughton wanted to publish, and were offering a contract for another two books about this detective Jim Meldrum. Almost by accident, I had the opportunity to do a series of crime novels featuring the same character. Now, four years later, I’ve had four Meldrum books published, and have just finished a fifth.”

“A study of integrity and what it cost” – there’s the thing “wherein we’ll catch the conscience of the king!”

I regard the world of Lindsay’s forlorn Inspector Jim Meldrum to be as intelligent and as perceptive of human behaviour as George’s Simenon’s Maigret. There’s no higher praise. I have one caveat: Meldrum is altered emotionally by his cases, whereas pipe smoking Maigret sighs deeply and moves on to the next. It’s a wonder Meldrum isn’t a psychological wreck.

Lindsay’s detective novels stand out not for their handling of police procedural detail, the stuff of the conventional thriller, but for their understanding of human nature. That includes a view of women as play things by powerful and deceitful men, often depicted in sordid scenes that grab the macho by the scrotum. As far as pointing out deplorable instances of misogyny, Lindsay was well ahead of the times.

It is not a surprise to learn BBC Scotland ignored him. No matter what book or adaptation was offered, all were declined – his work was infused with life under ‘benign’ colonial rule. He wasn’t perturbed. “BBC Scotland is an irrelevancy” he said.

Aside from approaches to BBC, his detective novels were not filmed for television. They merit a two-part series each defying conflation into an hour’s crime solved episode, and anyhow, BBC Scotland has never had a decent drama budget.

With his politics known there was no way BBC Scotland would touch his work. Indeed, it was Channel Four that funded his political thrill Brond through my film company, all of it shot in Glasgow. Brond was transmitted in the USA. I saw it as a national corrective to Scotch on the Rocks, the cheap thriller co-written by Tory MP Douglas Hurd, produced by BBC Scotland, broadcast just before the 1979 referendum on devolution.

In Hurd’s novel, hard-line nationalists are depicted as deluded fools or thugs. Lindsay, a writer who could pose searching questions about the state of Scottish politics and how badly they affect Scottish society, had no place in a BBC that had fired two competent director generals for daring to ask for a better deal for Scotland.

The bond of friendship between us never broke. We corresponded regularly while I was domiciled in Hollywood, me regaling him with experiences and anecdotes of Tinsel Town sleaze, and he keeping me up to date with Westminster’s shenanigans. I have those e-mails still. One told him of the clash Thomas Harris had with the director of Hannibal, the last in a trilogy of the flesh eating serial killer. Lindsay replied having read Hannibal:

“Not surprised to hear they butted heads – I can’t see how that ending can be filmed, not because of the eating brains stuff, you can write around that. No, because you can’t in a film take the battle of good and evil as embodied in Clarice and Lecter and have her made over to his taste – he can’t be Hannibal the cannibal and Svengali.

Even today audiences expect good winning out in the end in the same way a concert audience waits for the final chord to be resolved in the major key. I know there are counter examples, but usually there’s a redeeming feature. None in Hannibal, none in the novel. Harris gives him a wee sister who was eaten by an animal, reducing him from mythic monster to another product of a hard luck childhood.”

Lindsay was born in Glasgow in 1933, the son of a plumber father and teacher mother. On leaving North Kelvinside Secondary School, he worked as a library assistant in the Mitchell Library, (where he met his wife, Shirley) before studying at Glasgow University.

He got a first in English. That erudition, and an uncanny knowledge of the history of the independence movement, place Lindsay in a higher echelon than his contemporaries.

He served on literature committees, was actively involved with PEN and the Society of Authors, attended his local SNP group, and also wrote for theatre and radio. Moreover, I don’t recall him ever getting a bad review. I’m pleased I gave him my signed copy of Gore Vidal’s ‘Palimpsest’ a few months before he died.

I found Lindsay tremendously knowledgeable company, literate, wise, good humoured, and a damn stubborn cuss to deal with when it came to buying the rights to his books. His integrity was unassailable. It was near impossible to get him to say a bad word about other novelists let alone friends.

I have one of his stand-alone novels in screenplay form set in Scotland. If any BBC executive is reading this essay wracked with guilt for ignoring one of Scotland’s finest authors, now is the time for the corporation to redeem its wretched history – you have my address!

As for any reader planning to catch up on the best of Scottish authors, his novels are still available on Amazon; I recommend them all, some hardback covers reproduced among this essay. In 1975 he published a paperback of poems “And be a Nation Again’. Copies are on Amazon.

Prior to his death he was approached by a producer to write the screenplay for former British ambassador Craig Murray’s forthright account of torture and British complicity Murder in Samarkand. A great pity it was not made and released. It was a good match. Death cheated Lindsay out of his independence vote by a year, but then perhaps it was better he didn’t get confirmation of how craven are some of his countrymen.

Among his last words to me were, “Your polemic is superb, very readable. Publish it; you’ve an unmatched ability to coin a memorable well-honed phrase.” He said it as if he felt he should pass a compliment before it was too late to do so.

Like him, I eschew celebrity, hold tight to my privacy, and wish the world a better place. After some thought I did take one piece of his advice to hear, I started this essay site to help the cause of Scotland’s liberty. This homage is my belated thanks to a fine writer. Some people in life make you better than you might have been. He was one such friend.

Wherever Frederic Lindsay is now, I hope he has paper and pencil.

GB, this is soo-perb and inspirational.

I’m off to find ‘Brond’ on Amazon.

Best to you and yours for 2018!

I think every independista should have a copy of ‘Brond’ on their bookshelf! 🙂

Here’s to an exciting 2018!

Reblogged this on pictishbeastie.

Pingback: An Independent Novelist | pictishbeastie