An occasional series on eminent Scots ignored or forgotten.

Adrienne Corri – a talented actor, producer and author (1930 – 2016)

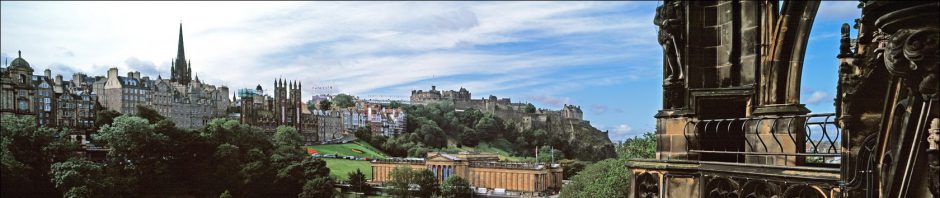

An Edinburgh Woman

I remember my disappointment turning to anger some years back when I read a published list of Scottish-born actors working in Hollywood compiled by the Scottish Film Fund, now part of profit-led Creative Scotland. It was such a poorly researched piece it deserved to be binned. Adrienne Corrie’s name was one not on the list.

Adrienne Corrie died aged 85. She was born Adrienne Riccoboni, with an Italian father, and educated in Edinburgh in the 1930s. As an independent mind, she was way ahead of her time in a profession dominated by men some of them predatory. Female artistes of outstanding ability are showing their metal these days, there are too few like Corrie.

Edinburgh was a reeky place back then, with horse-drawn trams still in existence. You’d hardly know of her birthplace even if you had noticed her brilliance, or followed her television and film appearances. Only male stars such as Connery get praise from their home town welcomed back to be given the Freedom of the City.

Corri was an actor of considerable range and versatility, as well as a quite beautiful woman. She had cheekbones you could perch a chocolate on- okay, she was an Italian Scot, it goes with the genes. As a theatre director, later film, I was keen to meet her but never had the role that would have been the perfect excuse to arrange it. (I got as far as a lengthy phone conversation.) To be frank, older than me, she’d have eaten me unsalted if she had detected the merest squelch of bullshit.

Corri was a feminist before feminism was a career choice. She hated directors who were cloying or patronising. She received fees half that of her male co-stars, had agents clever at writing small print that left her without repeat fees, and who took months to pay her.

If stereotypes have any truth to them, Corri’s magnificent red hair was a warning to the unwary. She was tempestuous.

Fire in her eyes

It was plain as the fire in her eyes she was wholly incompatible as a partner, and so it transpired for her two husbands, the last, actor Daniel Massey, whom she outlived. He probably handled her as the male Black Widow spider handles its far bigger mate, with a gift, a grab, and a dash for safety.

She didn’t hate men. In her early career she responded to men a lot, but rarely was the better for it. Were she still with us, her contemporary, the multi-talented Eartha Kit, would commiserate on the subject of the unreliability of the male species. Make swift use of them, and then flick ’em away.

For Corri it was less her love life that caused her anger, far more how she was used in his profession that so got under her skin. In one infamous television debate about women’s rights in the media, Corri got thoroughly scunnered with the carefully couched views of her female panellists. She tore off her neck microphone and stomped out the studio in the full view of the cameras. She would have given BBC’s Question Time one heck of a run for its money.

Her obvious talent, the passion she could bring to a role, a hot-blooded Mediterranean in a Scottish accent able to out-talk any man, was rarely handled well or with care by male directors. A disappointing professional life dominated by men, success infrequent, more lows than highs, hardens a woman’s capacity to accept the best in men at face value.

The young Corri’s breakout role in ‘The River‘

Early success

Her memorable best role, as with so many young actors, came early in her career. After a walk-on role in Quo Vadis (1951), shot in Rome, she was off to India to appear in her very best film, in my opinion, the one with the finest director, son of Renoir the painter, Jean Renoir. Like all good actors she responded to sensitive direction, but above all, to an excellent script. Actors need to believe in the script as much as we do.

The River (1951) is a poetic evocation of life among British colonials in post-second world war Bengal, a visual tour de force. Based on the novel by Rumer Godden, the film eloquently contrasts the growing pains of three young women with the immutability of the Bengal river around which their daily lives unfold. There are no fast cars, no explosions, no speeded-up fights.

Corri, her red hair standing out in splendid Technicolor, is the most mature, voluptuous and spoiled of three teenage girls, all suffering adolescent pangs for a young war hero. Corri gives a stand-out interpretation of a young woman on the cusp of womanhood, the subtlety and nuance she manages in one so new to acting is captivating. She is never cloying, or sentimental. There’s a lovely no-nonsense about her character. The River isn’t often on television, but I urge lovers of cinema to watch it if it does appear.

The reality of a male dominated industry

Sadly for such a bright talent, but par for the course in respect of Hollywood’s attitude to women roles are confined to ingénue, hooker, cookie airhead, or bored housewife – Corri is mainly remembered for her participation in the short but notorious gang rape scene from Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of Anthony Burgess’s dystopian novel, A Clockwork Orange (1971). In it she is ritualistically raped by a giant plastic penis shaped as a stool seat held aloft by Malcolm McDowall her attacker, while he dances to Singing In the Rain.

Despite complaining to Kubrick about the multitude of takes, Kubrick asked for more. He was notorious for manipulating his actors until their patience broke. (A few walked of set never to return.) He argued it caused them to shed any easy techniques, or quirks, or shallowness. By the end of the forty-eighth take on day five they must have been so knackered all Kubrick got was a sleep walking interpretation.

Adrienne Corri initially declined the role of Mrs. Alexander because Kubrick was getting applicants to de-bra in his office while he trained a video camera on them. She made it clear that wasn’t acceptable. “But Adrienne, suppose we don’t like the tits?”

Her answer was one word and to the point: “Tough.”

Despite Kubrick’s sleazy prurience Corri retained a friendship with the director for a while but it was wasted loyalty. He never offered her another role. Just the same, the scene is the one that stays in the imagination for its ferocity and graphic expression. One Christmas later she gave him a pair of bright red socks, a reference to the scene, in which she is left naked but for such garments.

The rape scene in ‘Clockwork Orange’, a notoriety moment

A working mother

As a single parent in the Sixties she succumbed to the need to support two children, a son and a daughter, by working for Hammer Horror movies in a succession of stupid, make ’em quick, pile ’em high films.

Her tenure began with Journey Into Darkness, 1968), and then as was The Viking Queen (1967), a silly sword-and-sandal half-baked epic, in which Corri was an anti-Roman pro-druid princess who snaps and snarls. In The Tell-Tale Heart (1960), adapted from Edgar Allan Poe’s story, a timid librarian is obsessed by Corri, the flower seller who lives across the street and who, like many horror-movie heroines, has a tendency to undress by a window without closing the curtains.

There were two films in which Corri bravely disguised her beauty: she played a disfigured prostitute in A Study in Terror (1965), which pitted Sherlock Holmes against Jack the Ripper, and in Madhouse (1974), she was bald and wore a mask to hide her face, mutilated in a car accident. There was other low budget pulp, and while one can claim she made a living, you can’t claim she made a reputation.

Working with the best directors

Later she took minor roles in bigger films, three in her friend Otto Preminger’s movies, Bunny Lake Is Missing (1965), Rosebud (1975) and The Human Factor (1979), and as the mother of Lara (Julie Christie) in David Lean’s Dr Zhivago (1965). Among her dozens of television parts were Milady de Winter in the BBC series of The Three Musketeers (1954) and various appearances in episodes of ABC’s Armchair Theatre (1956-60).

Corri didn’t waste her student days at RADA studying classic and Shakespearean roles. She also gained acclaim on stage – she was part of the Old Vic company (1962-63), and appeared on Broadway in Jean Anouih’s The Rehearsal (1963).

Smokin’ hot Corri, playing a movie star

Still a rebel

In 1959, rebellious to the end, she had a leading role in John Osborne’s The World of Paul Slickey, a bitter musical satire on the tabloid press, which received the ire of critics and public alike. On the first night, Corri gave the booing audience a two-fingered salute.

I’ll stop here. Lists of stuff are boring.

By the time Corri – the temptation here is to call her Adrienne – was at RADA her parents ran the Crown Hotel in Callandar, Perthshire. She recounts her days there and in Edinburgh as happy ones. She maintained a remarkably scandal free private life, but that incisive temper together with forever cast as the seductive women, had to have lost her too many roles in good films.

Corri’s autobiographical search for art

Adrienne the author

In 1984 she published a unique semi-autobiographical account of serendipity in her long career. The Search for Gainsborough begins with her spotting an early portrait of the actor-playwright David Garrick hanging in a dilapidated Birmingham theatre and, convinced it wasn’t by any amateur, she proceeds to prove it the work of the young Thomas Gainsborough. Most of the leading art experts sneered at her attribution, but she persisted. Who was she to tell art experts their job, and a woman too?!

She followed the trail with forensic skill, got access to Bank of England ledgers, and ultimately discovered the payment made to Gainsborough for the Garrick portrait. This find leads to a second portrait. In time the experts confirmed her intuition and research, two Gainsborough’s now reclaimed for posterity.

What makes the book such an absorbing read is it’s written in diary format. We move from Corri’s humdrum theatre commitments to bad hotels, to encounters with pompous experts of the art world, in between she trying to keep her domestic life intact, and endless efforts to unravel the documentation.

She’ll be missed, as they say

Perhaps she realised after forty a women’s acting career is artificially limited for after that book her appearances grew fewer and fewer. Only a few actresses stay at the top into their sixties and seventies.

I can’t think of another Scottish actress around at the moment with anything like Corri’s beauty or searing ardour. If there are, history repeats itself – the good roles are still few and far between, and an exciting woman’s best talent is sure to be left ignored.

And believe me, the worst thing you can do to a woman is ignore her!

Actually, it seems she was born in Glasgow…..

from ScotlandsPeople website:

Year Surname Forename Sex District City/County/ MR GROS Data

1931 RICCOBONI ADRIENNE F MILTON GLASGOW CITY/LANARK 644/09 0851

They didn’t even get her date of birth correct. Nor did they know her or speak to her. Sounds a bit like the old, close your eyes and stick a pin in, Scottish Film Fund. I checked on that lead and it has no substance. I don’t think she was long in Edinburgh, but did talk fondly of it, and indeed Scotland. It’s a shame we didn’t find plays or television dramas here for her to participate. I tried to find out from her agent if she had had any BBC Scotland offers, but got nowhere. BBC did give her a documentary on her discovery of the two Gainsborough portraits, and she got interviewed on the news and arts programmes. She was never ignored wherever she went … just in her homeland. But she was an expat of her time. The work barely existed here to sustain and develop talent. You went down south or wherever it took you.

Yep, and the Guardian made the same mistake with their Adrienne Corri obituary yesterday. Wikipedia has her birth date correct.

My starting point, after any personal experience I have, is the film actors archive, IMDB, but even that is sparse, now and again trips itself up by copying straight from error-strewn producer press releases. We should have our own Academy of the Moving Image.

Do we not have the building blocks for our own Academy of the Moving Image.? But is the question not bigger?

Given we have great resources like the RSC, Creative Scotland, GFT, regional Screen Scotland, two broadcasters STV and the BBC surely it’s surely not beyond the ken of man to have an overriding goal on developing a film industry, a progressive centre for performing arts as a Nation, I know we have a culture secretary, but I would like to see more joined up thinking, Film and TV productions only brought in £45 million in 2014, I honestly don’t think we are doing enough, in my humble opinion

There’s been many an attempt to set up a film studio, Connery most notable, although he denied Sony was all that interested.

The press pick up these stories and run with them without checking veracity. The celebrity aspect is cause enough to print half-baked proposals. Creative Scotland is doing its best to answer English companies based here who want a purpose built studio. But I’d want to know who is staying, and who should have support.

The fees from one of my political thrillers was used to put Glasgow’s Blackcat Studios into operation, more television-sized than film, but it failed for a second time in its short history. To be candid, without going into detail, I was very unhappy at the way I was side-lined although I had saved it from its first bankruptcy. I was, after all, the filmmaker with productions who could hire the studio. Headline: ‘Ego idiots crave kudos and dump the wrong man.’ Creating a national movie studio is a community effort. You get involved so everybody benefits.

There are two entities: an academy to record, research, encourage, and laud Scottish and Scottish based filmmakers of all kinds. A movie studio is a separate matter.

For that we need only four ’empty walls’ to hire out, a place near water and woods, and away from traffic and plane noise. Though it has to have a permanent lighting grid so production companies using it can hang their own lights, it also needs state of the art computers, and basic staff, plus security. That all costs ‘dead’ money, running costs.

But above all, we need a Scotia-orientated distribution company, plus guaranteed tie-in television deals to invest in, and transmit, films made before going to international sales. All those elements are London-based, and English culture biased.

These thoughts should have an essay of their own, and I might do it soon.