An essay in an occasional series on great Scots unjustly ignored

Camera shy Ian Stewart – the Jaguar driver – of Ecurie Ecosse

Observing Ian Stewart in the snug of a pub, tall rangy frame, in his eighties, Mount Rushmore of a nose, quiet, almost tranquil, a recent pacemaker operation, his beloved wife, Alex, no longer at his side, you’d be forgiven for thinking him a frail old chap, an ordinary man of no distinction.

But the perceptive spot something aristocratic in his bearing, a gentleman in the old definition. See him behind the steering wheel of a sports car and shallow judgement gets a red-hot poker of a prod. The gent in the corner nursing an orange juice is Ian Macpherson Stewart, lauded racing driver.

ECURIE ECOSSE

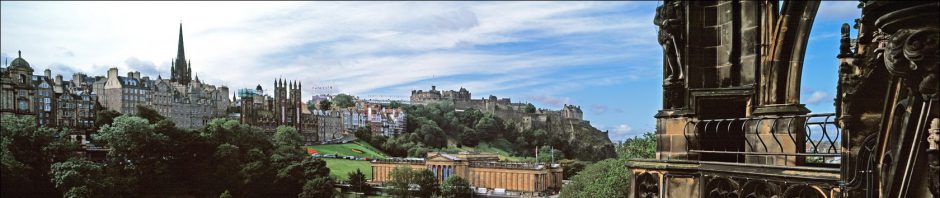

In 1951, together with businessman David Murray, mechanic Wilkie Wilkinson, and driver Bill Dobson, Stewart helped establish Ecurie Ecosse as a world class racing team, and all from a “pokie wee garage in a modest Edinburgh mews.”

The company was run less on a shoe string more a gob of gum, yet it managed to produce race winning Jaguars and lionhearted drivers. The team was the upstart to Jaguar’s own squad, a unique confluence of wealthy sponsor, clever mechanics, and gung-ho consummate drivers, plucky Scots to a man.

I met Stewart in the late autumn of his days, in the house he has lived most of his life, on a Perthshire bluff overlooking an abundant glen, the Highlands a grouse shoot away. It sits under sentinels of firs protecting it from razor raw Scottish winters. He converted it from a farmhouse himself, installing a swimming pool, laying the lawn, a resourceful man who could have put his hand to other careers had he not swooned to speed.

In an age of forced austerity, where cars are priced to attract Saudi princes, I questioned Stewart’s latter-day attitude. “Sometimes I find it hard to justify my passion for selfish cars, but I see them as a form of art, albeit entirely mechanical. We all have ways of expressing our creativity, and I can find no fault with someone who designs his dream and then tones it down to practical proposition. Creativity and slogging hard work can’t be bad!”

Now that time and fashion cloud acuity he might think himself a footnote in racing history unlike his former team mates, Jimmy and Jackie Stewart, Ron Flockhart, and Innes Ireland. There is some truth in that reflection due mainly to his early retirement.

YOUTHFUL AMBITIONS

“I wanted to fly Spitfires,” reflects Stewart with some emotion. “I was plane crazy.”

The air force told him a bare-faced lie; they said he was colour blind. Instead he did square bashing, sloping arms, and weapon’s maintenance. While polishing boots he dreamt of looping the loop in Perthshire skies, scaring sheep, dicing clouds as glutinous as frog spawn.

Demobbed, he did as his father commanded, went to agricultural college to prepare for a future working on his family’s cattle breeding farm. In that, he shared a background with Jim Clark, a Borders man, only Clark’s family looked after prime sheep not lowly cattle – there’s snobbery in farming as well as in cars.

IMPRINTING THE COMPULSION

His lust for sports cars was kindled by his mother’s MG TC. His school chum taught him to drive when Stewart was under age. Adrenalin rushes demand incremental boosts to repeat the highs; local drives soon gave way to hill climbs and track racing. Stewart learned driving a sports car fast. Driving skilfully fast engages all the senses, it made him happy, and happiness is a kind of intoxication.

His love of motor sports overtook interest in cattle insemination, silage, and crop rotation. Against dire patriarchal stricture he followed his heart’s desire alienating his father in the process, a wound that did not heal.

His father never attended a race, stubbornly refusing to acknowledge his son’s achievements. He did not recognise they shared the same obstinate gene. Without it Stewart might not have secured himself a piece of automotive history. Nevertheless, an honourable man, a good man, Stewart terminated his racing career early to look after his ailing father, the farm, and pubs they owned.

Stewart talks charitably about his days with Jaguar as a works driver. William (Bill) Lyons was generous, and charming, a family man, but when he wanted something he was “utterly dictatorial, his word law.”

Stewart agrees Lyons was born with an innate sense of mature aesthetics, one he applied with originality to car design. “Bill Haynes, Jaguar’s chief engineer, Lyons’ right-hand man, was “relentlessly earnest, a lot less outward going than Lyons.” There were long periods when neither Lyons and Haynes talked to each other though they lived a few miles apart. Seeing my disbelief he adds, “I was asked to intervene in one instance, to sweeten things. I declined. It wasn’t my place.”

There’s that gentleman again.

RACING FOR JAGUAR

He recalls racing for the Jaguar Works Team in 1952 and 1953, and how ineffective were the C-Type headlights, “Like glow-worms.” A drivers’ get-together during practice generated a request to Lyons for a swift remedy, but none arrived. It was a bad race for mist patches, especially on the Mulsanne straight. “We did three hour shifts. I had the dreaded 01.00 to 04.00 shift. On minute you could see, the next you couldn’t; no fun when you were following a Panhard travelling 50 mph slower!”

Of all his C-Type races he talks with nostalgia about the one against Stirling Moss at Charterhall, Scotland, in 1952. “I thought Stirling let me beat him, but he said he never let anyone beat him. If the race had lasted another couple of laps he’d have beaten me – I was clean out of brakes.” He pauses, introspectively. “You don’t admire racing drivers, you respect them. I had a wholesome respect for Stirling, got on well with Ninian Sanderson, Mike Hawthorn, Tommy Sopwith, and Roy Salvadori, but you must retain a belief in yourself, a belief that you can improve and improve. If you get into admiration you’re lost.”

FAVOURITE JAGUAR

C-Type aside, his favourite Jaguar is the E-Type. “It handled beautifully. Easy to throw around; the tail might snap out but you can control it.” Of the E-Type’s looks he opines, “We got a shock when we saw the concept. The nose was too long, the windscreen too upright. Bill Haynes wanted six more months of testing but clamour from press and public forced it into production before it was fully developed leaving early models with faults.”

Of the current Jaguar model range Stewart is circumspect. He feels Jaguar – now owned by mega-conglomerate, Tata – has yet to recapture the marque’s blue-blooded street presence. “The new is maybe a deliberate attempt to negate ostentation in an era where excess is ill-received; aimed at executives who want to avoid flamboyance. I always admired Jaguar’s all-round sheer excellence, but I am bound to add the models seem a great opportunity missed.” Of the F-Type he shakes his head diplomatically. Criticism cocooned in good manners is measurement with discretion.

Stewart’s attitude calls to mind motor sport of a past era, weekend racers festooned with flying jacket and goggles, faces smeared with oil, peering over an endless bonnet, leather capped heads doubling as a rudimentary roll bar. Stewart’s drive today is bang up to date, a Porsche Cayman S, his previous a Lotus Evora – “Almost a 911 beater,” he sighs, wishing Lotus had done just that bit better.

Ian Stewart is not known to drive sedately. His son, Christian, confirms his father’s bravura. “He takes corners by the seat of his pants. He throws himself into them, judging how to get out while there!”

THE SILENT HERO

What stories he could tell. But he eschews memoirs. “Nothing is farther from my thoughts.” Stewart is a man who looks forward to tomorrow.

Though it can be sad to get old, Ian Stewart has much to teach us.

He exemplifies an age where valour, honour, and gallantry were considered fine qualities. I am certain in years to come Perth roads will hear echoes of his straight six at full chat, scattering pheasants in all directions.

The anonymous elderly man in the quiet of the pub’s inglenook should not be underestimated. You don’t have to be flamboyant to be a hero.

******************************

To my shame I’d never heard of Ian Stewart, he really seems to be the embodiment of a hero. No bragging, no limelight seeking, just doing what he loved.

I remember Ian Stewart when he had his E Type, his Lancia, the 300 SL Gullwing Merc; still I remember the reg number! Two Porsche 911s and a Ford Thames van much modified!

I worked on all of them in a small way. Enjoyed the road tests even in the Mini. He used to say check petrol oil and water and bale it out inside!!

Great days for me. Good health Ian.

Thanks for your memories, Douglas. I’ll pass them on to Ian.